The Impermanence of Life

From Words of My Perfect Teacher:

Chapter 2

The Impermanence of Life

Seeing this threefold world as a fleeting illusion,

You have left this life’s concerns behind like spittle in the dust.

Accepting all hardships, you have followed in the footsteps of the masters of old.

Peerless Teacher, at your feet I bow.

The way to listen to the teaching is as described in Chapter One. The actual subject matter consists of seven meditations: the impermanence of the outer universe in which beings live, the impermanence of the beings living in it, the impermanence of holy beings, the impermanence of those in positions of power, other examples of impermanence, the uncertainty of the circumstances of death, and intense awareness of impermanence.

I. THE IMPERMANENCE OF THE OUTER UNIVERSE IN WHICH BEINGS LIVE

Our world, this outer environment fashioned by the collective good karma of beings, with its firm and solid structure encompassing the four continents, Mount Meru and the heavenly realms, lasts for a whole kalpa. It is nonetheless impermanent and will not escape final destruction by seven stages of fire and one of water.

As the present great kalpa draws closer to the time of destruction, the beings inhabiting each realm below the god-realm of the first meditative state will, realm by realm, progressively disappear until not a single being is left.

Then, one after the other, seven suns will rise in the sky. The first sun will burn up all fruit-bearing trees and forests. The second will evaporate all streams, creeks and ponds; the third will dry up all the rivers; and the fourth all the great lakes, even Manasarovar. As the fifth sun appears, the great oceans, too, will progressively evaporate at first to a depth of one hundred leagues, then of two hundred, seven hundred, one thousand, ten thousand, and finally eighty thousand leagues. The sea-water that is left will shrink from a league down to an ear-shot, until not even enough remains to fill a footprint. By the time there are six suns all blazing together, the entire earth and its snow-covered mountains will have burst into flames. And when the seventh appears, Mount Meru itself will burn up, together with the four continents, the eight sub-continents, the seven golden mountains, and the circular wall of mountains at the world’s very rim. Everything will fuse into one vast mass of fire. As it blazes downwards, it will consume all the infernal realms. As it flares upwards, will engulf the celestial palace of Brahma, already long abandoned. Above, the younger gods of the realm of Clear Light will cry out in fear, “What an immense conflagration!” But the older gods will reassure them, saying, “Have no fear! Once it reaches the world of Brahms, it will recede. This has happened before.”*

(*These stages of destruction all take place within one kalpa, but even these long-lived gods can grow old between the first destruction by fire and the seventh, after which their realm-part of that of the second concentration – will be destroyed by water.)

II. THE IMPERMANENCE OF BEINGS LIVING IN THE UNIVERSE

From the summit of the highest heavens to the very depths of hell, there is not a single being who can escape death. As the Letter of Consolation says:

Have you ever, on earth or in the heavens,

Seen a being born who will not die?

Or heard that such a thing had happened?

Or even suspected that it might?

Everything that is born is bound to die. Nobody has ever seen anyone or heard of anyone in any realm – even in the world of the gods – who was born but never died. In fact, it never even occurs to us to wonder whether a person will die or not. It is a certainty. Especially for us, born as we are at the end of an era* in a world where the length of life is unpredictable, death will come soon. It gets closer and closer from the moment we are born. Life can only get shorter, never longer. Inexorably, Death closes in, never pausing for an instant, like the shadow of a mountain at sunset.

(*The end of an era is a period of decline in which life is more fragile.)

Do you know for sure when you will die, or where? Might it be tomorrow, or tonight? Can you be sure that you are not going to die right now, between this breath and the next? As it says in The Collection of Deliberate Sayings:

Who’s sure he’ll live till tomorrow?

Today’s the time to be ready,

For the legions of Death

Are not on our side.

And Nagarjuna, too, says:

Life flickers in the flurries of a thousand ills,

More fragile than a bubble in a stream.

In sleep, each breath departs and is again drawn in;

How wondrous that we wake up living still!

Breathing gently, people enjoy their slumber. But between one breath and the next there is no guarantee that death will not slip in. To wake up in good health is an event which truly deserves to be considered miraculous, yet we take it completely for granted.

Although we know that we are going to die one day, we do not really let our attitudes to life be affected by the ever – present possibility of dying. We still spend all our time hoping and worrying about our future livelihood, as if we were going to live forever. We stay completely involved in our struggle for well-being, happiness and status-until, suddenly, we are confronted by Death wielding his black noose, gnashing ferociously at his lower lip and baring his fangs.

Then nothing can help us. No soldier’s army, no ruler’s decrees, no rich man’s wealth, no scholar’s brilliance, no beauty’s charms, no athlete’s fleetness-none is of any use. We might seal ourselves inside an impenetrable, armoured metal chest, guarded by hundreds of thousands of strong men bristling with sharp spears and arrows; but even that would not afford so much as a hair’s breadth of protection or concealment. Once the Lord of Death secures his black noose around our neck, our face begins to pale, our eyes glaze over with tears, our head and limbs go limp, and we are dragged willy-nilly down the highway to the next life.

Death cannot be fought off by any warrior, ordered away by the powerful, or paid off by the rich. Death leaves nowhere to run to, no place to hide, no refuge, no defender or guide. Death resists any recourse to skill or compassion. Once our life has run out, even if the Medicine Buddha himself were to appear in person he would be unable to delay our death.

So, reflect sincerely and meditate on how important it is from this very moment onwards never to slip into laziness and procrastination, but to practise the true Dharma, the only thing you can be sure will help at the moment of death.

III. THE IMPERMANENCE OF HOLY BEINGS

In the present Good Kalpa, Vipasyin, Sikhin and five other Buddhas have already appeared, each with his own circle of Sravakas and Arhats in inconceivable number. Each worked to bring benefit to innumerable beings through the teachings of the Three Vehicles. Yet nowadays all we have is whatever still remains of the Buddha Sakyamuni’s teaching. Otherwise, all of those Buddhas have passed into nirvana and all the pure Dharma teachings they gave have gradually disappeared.

One by one, the numerous great Sravakas of the present dispensation too, each with his entourage of five hundred Arhats, have passed beyond suffering into the state where nothing is left of the aggregates.

In India, there once lived the Five Hundred Arhats who compiled the words of the Buddha. There were the Six Ornaments and Two Supreme Ones, the Eighty Siddhas, and many others, who mastered all attributes of the paths and levels and possessed unlimited clairvoyance and miraculous powers. But all that remains of them today are the stories telling how they lived.

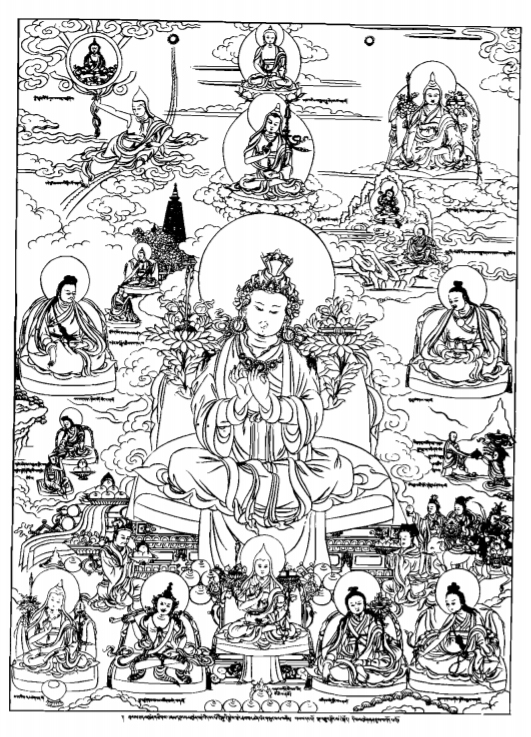

Here too in Tibet, the Land of Snows, when the Second Buddha of Oddiyana* turned the Wheel of Dharma to ripen and liberate beings, there lived all his followers, like the twenty-five disciples known as the King and Subjects and the Eighty Siddhas of Yerpa. Later came the Ancient Tradition masters of the So, Zur and Nub clans; Marpa, Milarepa and Dagpo of the New Tradition; and innumerable other learned and accomplished beings. Most oft hem achieved high levels of accomplishment and had mastery over the four elements. They could produce all sorts of miraculous transformations. They could make tangible objects appear out of nowhere and disappear into nowhere. They could not be burned by fire, be swept away by water, be crushed by earth or fall from precipices into space – they were simply free from any harm that the four elements could bring about.

(*Padmasambhava is often referred to as the second Buddha of our era, extending the work of Sakyamuni.)

Once, for example, Jetsun Milarepa was meditating in silence in Nyeshangkatya cave in Nepal when a band of hunters passed by. Seeing him sitting there, they asked him whether he was a man or a ghost. Milarepa remained motionless, his gaze fixed before him, and did not answer. The hunters shot a volley of poisoned arrows at him, but none of their arrows managed to pierce his skin. They threw him into the river, and then over the edge of a cliff-but each time there he was again, sitting back where he had been before. Finally, they piled firewood around him and set it alight, but the fire would not burn him. There have been many beings who attained such powers. But in the end, they all chose to demonstrate that everything is impermanent,* and today all that remains of them is their stories.

(*Such beings are considered to be beyond birth and death. However, like the Buddha Sakyamuni, they choose to die nonetheless to remind beings of impermanence.)

As for us, our negative actions, carried along by the wind of negative conditions in the prevailing direction of our negative tendencies, have driven us here into this filthy contraption made up of the four material elements, in which we are trapped and upon which our sentient existence depends – and as we can never be sure when or where this scarecrow of an illusory body is going to disintegrate, it is important that from this very moment onwards we inspire ourselves to thoughts, words and deeds which are always positive. With this in mind, meditate on impermanence.

IV. THE IMPERMANENCE OF THOSE IN POSITIONS OF POWER

There are magnificent and illustrious gods and risis who can live for as long as a kalpa. But even they cannot escape death. Those who rule over beings, like Brahma, Indra, Visnu, Isvara and other great gods living for a whole kalpa, with statures measured in leagues or earshots and a power and resplendence that outshine the sun and moon, are nevertheless not beyond the reach of death. As The Treasury of Qualities says:

Even Brahma, Indra, Mahesvara and the universal monarchs

Have no way to evade the Demon of Death.

In the end, not even divine or human risis with the five kinds of clairvoyance and the power to fly through the sky can escape death. The Letter of Consolation says:

Great risis with their five-fold powers

Can fly far and wide in the skies,

Yet they will never reach a land

Where immortality holds sway.

Here in our human world there have been universal emperors who have reached the very pinnacle of power and material wealth. In the holy land of India, starting with Mahasarnmata, innumerable emperors ruled the entire continent. Later the three Palas, the thirty-seven Candras and many other rich and powerful kings reigned in both eastern and western India.

In Tibet, the Land of Snows, the first king, Nyatri Tsenpo, was of divine descent, an emanation of the Bodhisattva Nivaranaviskambhin. Then reigned the seven heavenly kings called Tri, the six earthly kings called Lek, the eight middle kings called De, the five linking kings called Tsen, the twelve and a half* kings of the Fortunate Dynasty including the five of the Extremely Fortunate Dynasty, and others besides. In the reign of the Dharma King Songtsen Gampo, a magical army subdued all lands from Nepal to China. King Trisong Detsen brought two thirds of Jambudvipa** under his power, and, during the reign of Ralpachen, an iron pillar was erected on the banks of the Ganges, marking the frontier between India and Tibet. Tibet exercised power in many regions of India, China, Gesar, Tajikistan and other countries. At the New Year festival, ambassadors from all those countries were required to spend one day in Lhasa. Such was Tibet’s power in the past. But it did not last, and nowadays, apart from the historical accounts, nothing is left.

(*The “half” refers to the reign of Mune Tsenpo, who died after reigning for only one year and nine months.)

(**Here this term would seem to refer to South Asia, Mongolia and China.)

Reflect on those past splendours. Compared to them, our own homes, belongings, servants, status, and whatever else we prize, seen! altogether no more significant than a beehive. Meditate deeply, and ask yourself how you could have thought that those things would last forever and never change.

V. OTHER EXAMPLES OF IMPERMANENCE

As an example of impermanence, consider the cycle of growth and decline that takes place over a kalpa. Long ago, in the first age of this kalpa, there were no sun and moon in the sky and all human beings were lit up by their own intrinsic radiance. They could move miraculously through space. They were several leagues tall. They fed on divine nectar and enjoyed perfect happiness and well-being, matching that of the gods. Gradually, however, under the influence of negative emotions and wrong-doing, the human race slowly degenerated to its present state. Even today, as those emotions become ever more gross, human lifespan and good fortune are still on the decrease. This process will continue until humans live no more than ten years. Most of the beings living in the world will disappear during periods of plague, war and famine. Then, to the survivors, an emanation of the Buddha Maitreya will preach abstinence from killing. At that time, humans will only be one cubit tall. From then on their lifespan will increase to twenty years and then gradually become longer and longer until it reaches eighty thousand years. At that point Lord Maitreya will appear in person, become Buddha and turn the Wheel of the Dharma. When eighteen such cycles of growth and decline have taken place and human beings live an incalculable number of years, the Buddha Infinite Aspiration will appear and live for as long as all the other thousand Buddhas of the Good Kalpa put together. His activities for beings’ welfare, too, will match all of theirs put together. finally, this kalpa will end in destruction. Examining such changes, you can see that even on this vast scale nothing is beyond the reach of impermanence.

Watching the four seasons change, also, you can see how everything is impermanent. In summertime the meadows are green and lush from the nectar of summer showers, and all living beings bask in a glow of well being and happiness. Innumerable varieties of flowers spring up and the whole landscape blossoms into a heavenly paradise of white and gold, scarlet and blue. Then, as the autumn breezes grow cooler, the green grasslands change hue. Fruit and flowers, one by one, dry up and wither. Winter soon sets in, and the whole earth becomes as hard and brittle as rock. Ponds and rivers freeze solid and glacial winds scour the landscape. You could ride for days on end looking for all those summer flowers and never see a single one. And so comes each season in turn, summer giving way to autumn, autumn to winter and winter to spring, each different from the one before, and each just as ephemeral. Look how quickly yesterday and today, this morning and tonight, this year and next year, all pass by one after the other. Nothing ever lasts, nothing is dependable.

Think about your village or monastic community, or wherever you live. People who not long ago were prosperous and secure now suddenly find themselves heading for ruin; others, once poor and helpless, now speak with authority and are powerful and wealthy. Nothing stays the same forever. In your own family, each successive generation of parents, grandparents and great-grandparents have all died, one by one. They are only names to you now. And as their time came many brothers, sisters and other relatives have died too, and no-one knows where they went or where they are now. Of the powerful, rich and prosperous people who only last year were the most eminent in the land, many this year are already just names. Who knows whether those whose present wealth and importance makes them the envy of ordinary folk will still be in the same position this time next year-or even next month? Of your own domestic animals-sheep, goats, dogs-how many have died in the past and how many are still alive? When you think about what happens in all of these cases, you can see that nothing stays the same forever. Of all the people who were alive more than a hundred years ago, not a single one has escaped death. And in another hundred years from now, every single person now alive throughout the world will be dead. Not one of them will be left.

There is therefore absolutely nothing in the universe, animate o inanimate, that has any stability or permanence.

Whatever is born is impermanent and is bound to die.

Whatever is stored up is impermanent and is bound to run out.

Whatever comes together is impermanent and is bound to come apart.

Whatever is built is impermanent and is bound to collapse.

Whatever rises up is impermanent and is bound to fall down.

So also, friendship and enmity, fortune and sorrow, good and evil, all the thoughts that run through your mind-everything is always changing.

You might be as exalted as the heavens, as mighty as a thunderbolt, as rich as a naga, as good-looking as a god or as pretty as a rainbow – but no matter who or what you are, when death suddenly comes there is nothing you can do about it for even a moment. You have no choice but to go, naked and cold, your empty hands clenched stiffly under your armpits. Unbearable though it might be to part with your money, your cherished possessions, your friends, loved ones, attendants, disciples, country, lands, subjects, property, food, drink and wealth, you just have to leave everything behind, like a hair being pulled out of a slab of butter.* You might be the head lama over thousands of monks, but you cannot take even one of them with you. You might be governor over tens of thousands of people, but you cannot take a single one as your servant. All the wealth in the world would still not give you the power to take as much as a needle and thread,

(*The butter does not stick to the hair. Only the empty impression of the hair remains.)

Your dearly beloved body, too, is going to be left behind. This same body that was wrapped up during life in silk and brocades, that was kept well filled up with tea and beer, and that once looked as handsome and distinguished as a god, is now called a corpse, and is left lying there horribly livid, heavy and distorted. Says Jetsun Mila:

This thing we call a corpse, so fearful to behold,

Is already right here – our own body.

Your body is trussed up with a rope and covered with a curtain, held in place with earth and stones. Your bowl is turned upside down on your pillow. No matter how precious and well loved you were, now you arouse horror and nausea. When the living lie down to sleep, even on piles of furs and soft sheepskin rugs, they start to feel uncomfortable after a while and have to keep turning over. But once you are dead, you just lie there with your cheek against a stone or tuft of grass, your hair bespattered with earth.

Some of you who are heads of families or clan chiefs might worry about the people under your care. Once you are no longer there to look after them, might they not easily die of hunger or cold, be murdered by enemies, or drown in the river? Does not all their wealth, comfort and happiness depend on you? In fact, however, after your death they will feel nothing but relief at having managed to get rid of your corpse by cremating it, throwing it into a river, or dumping it in the cemetery.

When you die, you have no choice but to wander all alone in the intermediate state without a single companion. At that time your only refuge will be the Dharma. So tell yourself again and again that from now on you must make the effort to accomplish at least one practice of genuine Dharma.

Whatever is stored up is bound to run out. A king might rule the whole world and still end up as a vagabond. Many start their life surrounded by wealth and end it starving to death, having lost everything. People who had herds of hundreds of animals one year can be reduced to beggary the next by epidemics or heavy snow, and someone who was rich and powerful only the day before might suddenly find himself asking for alms because his enemies have destroyed everything he owns. That all these things happen is something you can see for yourself; it is impossible to hang on to your wealth and possessions forever. Never forget that generosity is the most important capital to build up.

No coming together can last forever. It will always end in separation. We are like inhabitants of different places gathering in thousands and even tens of thousands for a big market or an important religious festival, only to part again as each returns home. Whatever affectionate relationships we now enjoy-teachers and disciples, masters and servants, patrons and their proteges, spiritual comrades, brothers and sisters, husbands and wives – there is no way we can avoid being separated in the end. We cannot even be sure that death or some other terrible event might not suddenly part us right now. Since spiritual companions, couples and so forth might be split up unexpectedly at any moment, we had better avoid anger and quarrels, harsh words and fighting. We never know how long we might be together, so we should make up our minds to be caring and affectionate for the short while that we have left. As Padampa Sangye says:

Families are as fleeting as a crowd on market-day;

People of Tingri, don’t bicker or fight!

Whatever buildings are constructed are bound to collapse. Villages and monasteries that were once successful and prosperous now lie empty and abandoned, and where once their careful owners lived, now only birds make their nests. Even Samye’s central three-storeyed temple, built by miraculously emanated workers during the reign of King Trisong Detsen and consecrated by the Second Buddha of Oddiyana, was destroyed by fire in a single night. The Red Mountain Palace that existed in King Songtsen Gampo’s time rivalled the palace of Indra himself, but now not even the foundation stones are left. In comparison, our own present towns, houses and monasteries are just so many insects’ nests. So why do we attach such importance to them? It would be better to set our hearts on following to the very end the example of the Kagyupas of old, who left their homeland behind and headed for the wilderness. They dwelt at the foot of rocky cliffs with only wild animals for companions, and, without the least concern about food, clothing or renown, embraced the four basic aims of the Kadampas:

Base your mind on the Dharma,

Base your Dharma on a humble life,

Base your humble life on the thought of death,

Base your death on an empty, barren hollow.*

(*Die alone in a remote place where there are no disturbances.)

High estate and mighty armies never last. Mandhatri, the universal king, turned the golden wheel that gave him power over four continents; he reigned over the heavens of the Gods of the Thirty-three; he even shared the throne of Indra, king of the gods, and could defeat the asuras in battle. Yet finally he fell to earth and died, his ambitions still unsatisfied. You can see for yourself that of all those who wield power and authority whether around kings, lamas, lords or governments-not a single one can keep his position forever; and that many powerful people, who have been imposing the law on others one year, find themselves spending the next languishing in prison. What use could such transitory power be to you? The state of perfect Buddhahood, on the other hand, can never diminish or be spoiled, and is worthy of the offerings of gods and men. That is what you should be determined to attain.

Friendship and enmity, too, are far from everlasting. One day while the Arhat Katyayana was out on his alms-round he came across a man with a child on his lap. The man was eating a fish with great relish, and throwing stones at a bitch that was trying to get at the bones. What the master saw with his clairvoyance, however, was this. The fish had been the man’s own father in that very lifetime, and the bitch had been his mother. An enemy he had killed in a past existence had been reborn as his son, as the karmic repayment for the life the man had taken. Katyayana cried out:

He eats his father’s flesh, he beats his mother off,

He dandles on his lap the enemy that he killed;

The wife is gnawing at her husband’s bones.

I laugh to see what happens in samsara’s show!

Even within one lifetime, it often happens that sworn enemies are later reconciled and make friends. They may even become part of each other’s families, and end up closer than anyone else. On the other hand, people intimately linked by blood or marriage often argue and do each other as much harm as they can for the sake of some trivial possession or paltry inheritance. Couples or dear friends can break up for the most insignificant reasons, ending sometimes even in murder. Seeing that all friendship and enmity is so ephemeral, remind yourself over and over again to treat everyone with love and compassion.

Good fortune and deprivation never last forever. There are many people who have started life in comfort and plenty, and ended up in poverty and suffering. Others start out in utter misery and are later happy and well off. There have even been people who started out as beggars and ended up as kings. There are countless examples of such reversals of fortune. Milarepa’s uncle, for instance, gave a merry party one morning for his daughter in-law, but by nightfall his house had collapsed and he was weeping with sorrow. When Dharma brings you hardships, then however many different kinds of suffering you might have to undergo, like Jetsun Mila and the Conquerors oft he past, in the end your happiness will be unparalleled. But when wrong-doing makes you rich, then whatever pleasure you might temporarily obtain, in the end your suffering will be infinite.

Fortune and sorrow are so unpredictable. Long ago in the kingdom of Aparantaka there was a rain of grain lasting seven days, followed by a rain of clothes for another seven days and a rain of precious jewels for seven days more-and finally there was a rain of earth which buried the entire population, and everyone died and was reborn in the lower realms. It is no use trying, full of hopes and fears, to control such ever-changing happiness and suffering. Instead, simply leave all the comforts, wealth and pleasures of this world behind, like so much spittle in the dust. Resolve to follow in the footsteps of the Conquerors of the past, accepting courageously whatever hardships you have to suffer for the sake of the Dharma.

Excellence and mediocrity are impermanent, too. In worldly life, however authoritative and eloquent you may be, however erudite and talented, however strong and skilful, the time comes when those qualities decline. Once the merit you have accumulated in the past is exhausted, everything you think is contentious and nothing you do succeeds. You are criticized from all sides. You grow miserable and everyone despises you. Some people lose whatever meagre advantages they once had and end up without any at all. Others, once considered cheats and liars with neither talent nor common-sense, later find themselves rich and comfortable, trusted by everyone and esteemed as good and reliable people. As the proverb says, “Aging frauds take pride of place.”

In religious life, too, as the saying goes, “In old age, sages become pupils, renunciates amass wealth, preceptors become heads of families.” People who early in life renounced all worldly activities may be found busily piling up riches and provisions at the end. Others start out teaching and explaining the Dharma but end up as hunters, thieves or robbers. Learned monastic preceptors who in their youth kept all the Vinaya vows may in their old age beget many children. On the other hand, there are also many people who spend all their earlier years doing only wrong but who, in the end, devote themselves entirely to practising the holy Dharma and either attain accomplishment or, if not, at least by being on the path when they die go on to higher and higher rebirths.

Whether someone appears to be good or bad just at present, therefore, is but a momentary impression that has no permanence or stability whatsoever. You might feel slightly disenchanted with samsara, develop a vague determination to be free of it, and take on the semblance of a serious student of Dharma to the point that ordinary folk are quite impressed, and want to be your patrons and disciples. But at that point, unless you take a very rigorous look at yourself, you could easily start thinking you really are as other people see you. Puffed up with pride, you get completely carried away by appearances and start to think that you can do whatever you want. You have been completely tricked by negative forces. So, banish all self-centred beliefs and arouse the wisdom of egolessness.* Until you attain the sublime Bodhisattva levels, no appearance, whether good or bad, can ever last. Meditate constantly on death and impermanence. Analyze your own faults and always take the lowest place. Cultivate dissatisfaction with samsara and desire for liberation. Train yourself to become peaceful, disciplined and conscientious. Constantly develop a sense of poignant and deep sadness at the thought of the transitoriness of all compounded things and the sufferings of samsara, like Jetsun Milarepa:

In a rocky cave in a deserted land

My sorrow is unrelenting.

Constantly I yearn for you,

My teacher, Buddha of the three times.

(*The wisdom that sees the emptiness of self and phenomena.)

Unless you maintain this experience constantly, there is no knowing where all the constantly changing thoughts that crop up will lead. There was once a man who, after having a feud with his relatives, took up the Dharma and became known as Gelong Thangpa the Practitioner. He learned to control energy and mind,* and was able to fly in the sky. One day, watching a large flock of pigeons gathering to eat the offering food he had put out, the thought occurred to him that with an army of as many men he could exterminate his enemies. He failed to take this wrong thought on the path,** and as a result when he finally returned to his homeland he became commander of an army.

(*He could control his mind in the sense of developing concentration but not in the sense of mastering the negative emotions or realising the nature of mind. From the point of view of Dharma, meditation without the proper orientation is useless.)

(**To take on the path. This means using all situations in daily life as part of the practice. If Gelong Thangpa had taken his negative thoughts on the path by using love as the antidote to aggression, for example, or by seeing the empty nature of the thought as soon as it arose, it would not have led to any harm.)

For the moment, thanks to your teacher and your spiritual companions, you might have a superficial feeling for the Dharma. But bearing in mind what a short time anyone person’s sentiments last, free yourself with the Dharma while you can, and resolve to practise as long as you live.

If you reflect on the numerous examples given here, you will have no doubt that nothing, from the highest states of existence down to the lowest hells, has even a scrap of permanence or stability. Everything is subject to change, everything waxes and wanes.

VI. THE UNCERTAINTY OF THE CIRCUMSTANCES* OF DEATH

(*The auxiliary cause which allows the deep cause to produce its effect. If someone dies in an accident, for instance, the accident itself, the circumstances of that death, and the deep cause, is a negative action performed in the past, of which death is the karmic result.)

Once born, every human in the world is sure to die. But how, why, when and where we are going to die cannot be predicted. None of us can say for sure that our death will come about at a particular time or place, in a certain way, or as a result of this or that cause.

There are few things in this world that favour life and many that threaten it, as the master Aryadeva points out:

Causes of death are numerous;

Causes of life are few,

And even they may become causes of death.

Fire, water, poisons, precipices, savages, wild beasts-all manner of mortal dangers abound, but only very few things can prolong life. Even food, clothing and other things usually considered life sustaining can at times turn into causes of death. Many fatalities occur as a result of eating – the food might be contaminated; or it may be something eaten for its beneficial properties but becoming toxic under certain circumstances;* or it might be the wrong food for a particular individual. Especially, nowadays most people crave meat and consume flesh and blood without a second thought, completely oblivious to all the diseases caused by old meat** or harmful meat spirits. Unhealthy diets and lifestyles can also give rise to tumours, disorders of phlegm, dropsy and other diseases, causing innumerable deaths. Similarly, the quest for riches, fame and other glories incites people to fight battles, to brave wild beasts, to cross rivers recklessly and to risk countless other situations that may bring about their demise.

(*In Tibetan medicine, this expression refers to foods which are healthy in themselves, but which become toxic or indigestible when eaten in combination with certain other foods.)

(**This means meat which is excessively old but not necessarily rotten. Food can be stored for long periods of time in Tibet because of the very particular climatic conditions.)

Furthermore, the moment when any of those numerous different causes of death might intervene is entirely unpredictable. Some die in their mother’s womb, some at birth, others before they learn to crawl. Some die young; others die old and decrepit. Some die before they can get medicine or help. Others linger on, glued to their beds by years of disease, watching the living with the eyes of the dead; by the time they die, they are just skeletons wrapped in skin. Many people die suddenly or by accident, while eating, talking or working. Some even take their own lives.

Surrounded by so many causes of death, your life has as little chance of enduring as a candle-flame in the wind. There is no guarantee that death will not suddenly strike right now, and that tomorrow you will not be reborn as an animal with horns on its head or tusks in its mouth. You should be quite sure that when you are going to die is unpredictable and that there is no knowing where you will be born next.

VII. INTENSE AWARENESS OF IMPERMANENCE

Meditate single-mindedly on death, all the time and in every circumstance. While standing up, sitting or lying down, tell yourself: “This is my last act in this world,” and meditate on it with utter conviction. On your way to wherever you might be going, say to yourself: “Maybe I will die there. There is no certainty that I will ever come back.” When you set out on a journey or pause to rest, ask yourself: “Will I die here?” Wherever you are, you should wonder if this might be where you die. At night, when you lie down, ask yourself whether you might die in bed during the night or whether you can be sure that you are going to get up in the morning. When you rise, ask yourself whether you might die sometime during the day, and reflect that there is no certainty at all that you will be going to bed in the evening.

Meditate only on death, earnestly and from the core of your heart. Practise like the Kadampa Geshes of old, who were always thinking about death at every moment. At night they would turn their bowls upside-down;* and, thinking how the next day there might be no need to light a fire, they would never cover the embers for the night.

(*Turning someone’s bowl over was for Tibetans a symbol that the person had died.)

However, just to meditate on death will not suffice. The only thing of any use at the moment of death is the Dharma, so you also need to encourage yourself to practise in an authentic way, never slipping into forgetfulness or loss of vigilance, remembering always that the activities of samsara are transient and without the slightest meaning. In essence, this conjunction of body and mind is impermanent, so do not count on it as your own; it is only on loan.

All roads and paths are impermanent, so whenever you are walking anywhere direct your steps toward the Dharma. As it says in the Condensed Transcendent Wisdom:

If you walk looking mindfully one yoke’s-length in front of you, your mind will not be confused.

Wherever you are, all places are impermanent, so keep the pure Buddhafields in mind. Food, drink and whatever you enjoy are impermanent, so feed on profound concentration. Sleep is impermanent, so while you are asleep purify sleep’s delusions into clear light.* Wealth, if you have it, is impermanent, so strive for the seven noble riches.** Loved ones, friends and family are impermanent, so in a solitary place arouse the desire for liberation. High rank and celebrity are impermanent, so always take a lowly position. Speech is impermanent, so inspire yourself to recite mantras and prayers. Faith and desire for liberation are impermanent, so strive to make your commitments unshakeable. Ideas and thoughts are impermanent, so work on developing a good nature. Meditative experiences and realizations are impermanent, so go on until you reach the point where everything dissolves in the nature of reality. At that time, the link between death and rebirth*** falls away and you reach such confidence that you are completely ready for death. You have captured the citadel of immortality; you are like the eagle free to soar in the heights of the heavens. After that there is no need for any sorrowful meditation on your approaching death.

(*If in one’s sleep one can remain focused on the clear light which is the natural manifestation of primal awareness, all one’s mental experiences will mingle with it and will not be perceived in a deluded fashion.)

(**Faith, discipline, learning, generosity, conscientiousness, modesty and wisdom.)

(***Death will not be followed by an ordinary automatic rebirth caused by past actions.)

As Jetsun Mila sang:

Fearing death, I went to the mountains.

Over and over again I meditated on death’s unpredictable coming,

And took the stronghold of the deathless unchanging nature.

Now I have lost and gone beyond all fear of dying!

And the peerless Dagpo Rinpoche says:

At first you should be driven by a fear of birth and death like a stag escaping from a trap. In the middle, you should have nothing to regret even if you die, like a farmer who has carefully worked his fields. In the end, you should feel relieved and happy, like a person who has just completed a formidable task.

At first, you should know that there is no time to waste, like someone dangerously wounded by an arrow. In the middle, you should meditate on death without thinking of anything else, like a mother whose only child has died. In the end, you should know that there is nothing left to do, like a shepherd whose flocks have been driven off by his enemies.

Meditate single-mindedly on death and impermanence until you reach that stage.

The Buddha said:

To meditate persistently on impermanence is to make offerings to all the Buddhas.

To meditate persistently on impermanence is to be rescued from suffering by all the Buddhas.

To meditate persistently on impermanence is to be guided by all the Buddhas.

To meditate persistently on impermanence is to be blessed by all the Buddhas.

Of all footprints, the elephant’s are outstanding; just so, of all subjects of meditation for a follower of the Buddhas, the idea of impermanence is unsurpassed.

And he said in the Vinaya:

To remember for an instant the impermanence of all compounded things is greater than giving food and offerings to a hundred of my disciples who are perfect vessels,* such as the bhiksus Sariputra and Maudgalyayana,

(*Perfectly capable of receiving the teachings correctly and making use of them.)

A lay disciple asked Geshe Potowa which Dharma practice was the most important if one had to choose only one. The Geshe replied:

If you want to use a single Dharma practice, to meditate on impermanence is the most important.

At first meditation on death and impermanence makes you take up the Dharma; in the middle it conduces to positive practice; in the end it helps you realize the sameness of all phenomena.

At first meditation on impermanence makes you cut your ties with the things of this life; in the middle it conduces to your casting off all clinging to samsara; in the end it helps you take up the path of nirvana.

At first meditation on impermanence makes you develop faith; in the middle it conduces to diligence in your practice; in the end it helps you give birth to wisdom.

At first meditation on impermanence, until you are fully convinced, makes you search for the Dharma; in the middle it conduces to practice; in the end it helps you attain the ultimate goal.

At first meditation on impermanence, until you are fully convinced, makes you practise with a diligence which protects you like armour; in the middle it conduces to your practising with a diligence in action; in the end it helps you practise with a diligence that is insariable.*

(*There are three types of diligence. When you have armour-like diligence, nothing can prevent you starting. When you have diligence in action, nothing can interrupt what you are doing. When you have diligence that cannot be stopped, nothing can stop you attaining your goal.)

And Padampa Sangye says:

At first, to be fully convinced of impermanence makes you take up the Dharma; in the middle it whips up your diligence; and in the end it brings you to the radiant dharmakaya.

Unless you feel this sincere conviction in the principle of impermanence, any teaching you might think you have received and put into practice will just make you more and more impervious* to the Dharma.

(*Someone who has not been tamed by the Dharma. He knows the Dharma but, not having practised it, his mind has become stiff. If one approaches Dharma with the wrong attitude, one can acquire a false self-confidence which makes one unreceptive to the teacher and the teachings.)

Padampa Sangye also said:

I never see a single Tibetan practitioner who thinks about dying;

Nor have I ever seen one live forever!

Judging by their relish for amassing wealth once they don the yellow robe, I wonder, Are they going to payoff Death in food and money?

Seeing the way they collect the best of valuables, I wonder Are they going to hand out bribes in hell?

Ha-ha! To see those Tibetan practitioners makes me laugh!

The most learned are the proudest,

The best meditators pile up provisions and riches,

The solitary hermits engross themselves in trivial pursuits,

The renunciates of home and country know no shame.

Those people are immune to the Dharma!

They revel in wrong-doing.

They can see others dying but have not understood that they themselves are also going to die.

That is their first mistake.

Meditation on impermanence is therefore the prelude that opens the way to all practices of Dharma. When he was asked for instructions on how to dispel adverse circumstances, Geshe Potowa answered with the following words:

Think about death and impermanence for a long time. Once you are certain that you are going to die, you will no longer find it hard to put aside harmful actions, nor difficult to do what is right. After that, meditate for a long time on love and compassion. Once love fills your heart you will no longer find it hard to act for the benefit of others. Then meditate for a long time on emptiness, the natural state of all phenomena. Once you fully understand emptiness, you will no longer find it hard to dispel all your delusions.

Once we have such conviction about impermanence, all the ordinary activities of this life come to seem as profoundly abhorrent as a greasy meal does to someone suffering from nausea. My revered Master often used to say:

Whatever I see of high rank, power, wealth or beauty in this world arouses no desire in me. That is because, seeing how the noble beings of old spent their lives, I have just a little understanding of impermanence. I have no deeper instruction than this to offer you.

So, just how deeply have you become permeated with this thought of impermanence? You should be like Geshe Kharak Gomchung, who went to meditate in the mountain solitudes of Jomo Kharak in the province of Tsang. In front of his cave there was a thorn-bush which kept catching on his clothes.

At first he thought, “Maybe I should cut it down,” but then he said to himself, “But after all, I may die inside this cave. I really cannot say whether I shall ever come out again alive. Obviously it is more important for me to get on with my practice.”

When he came back out, he had the same problem with the thorns. This time he thought, “I am not at all sure that I shall ever go back inside;” and so it went on for many years until he was an accomplished master. When he left, the bush was still uncut.

Rigdzin Jigme Lingpa would always spend the time of the constellation Risi, in autumn, at a certain hot spring. The sides of the pool had no steps, making it very difficult for him to climb down to the water and sit in it. His followers offered to cut some steps, but he replied: “Why take so much trouble when we don’t know if we will be around next year?” He would always be speaking of impermanence like that, my Master told me.

We too, as long as we have not fully assimilated such an attitude, should meditate on it. Start by generating bodhicitta, and as the main practice train your mind by all these various means until impermanence really permeates your every thought. Finally, conclude by sealing the practice with the dedication of merit. Practising in this way, strive to the best of your ability to emulate the great beings of the past.

Impermanence is everywhere, yet I still think things will last.

I have reached the gates of old age, yet I still pretend I am young.

Bless me and misguided beings like me,

That we may truly understand impermanence.

Jigme Lingpa (1729-1798)

(Jigme Lingpa received the transmission of the Heart-essence of the Vast Expanse from Longchenpa. He practised them in solitude and subsequently transmitted them to his own students.)

King Trisong Detsen (790-844)

(The king who invited the scholar Santaraksita and the Tantric master Padmasambhava to Tibet. He built Samye, Tibet’s first monastery, and was responsible for establishing the Buddhist teachings on a firm basis.)