How to Follow a Spiritual Friend

From ‘Words of my Perfect Teacher’:

Chapter Six

How To Follow a Spiritual Friend

No sutra, tantra or sastra speaks of any being ever attaining perfect Buddhahood without having followed a spiritual teacher. We can see for ourselves that nobody has ever developed the accomplishments belonging to the stages and paths by means of their own ingenuity and prowess. Indeed, all beings, ourselves included, show particular talent in discovering wrong paths to take – while when it comes to following the path leading to liberation and omniscience we are as confused as a blind person wandering alone in the middle of a deserted plain.

No-one can bring back jewels from a treasure island without relying on an experienced navigator.* Likewise, a spiritual teacher or companion is our true guide to liberation and omniscience, and we must follow him with respect. This is accomplished in three phases: firstly, by examining the teacher, then by following him, and finally by emulating his realization and his actions.

1. EXAMINING THE TEACHER

Ordinary people like us are, for the most part, easily influenced by the people and circumstances around us. That is why we should always follow a teacher, a spiritual friend.

(*A reference to adventurers in ancient times who went to seek jewels in faraway islands.)

In the sandalwood forests of the Malaya mountains, when an ordinary tree falls, its wood is gradually impregnated with the sweet perfume of the sandal. After some years that ordinary wood comes to smell as sweet as the sandal trees around it. In just the same way, if you live and study with a perfect teacher full of good qualities, you will be permeated by the perfume of those qualities and in everything you do you will come to resemble him.

Just as the trunk of an ordinary tree

Lying in the forests of the Malaya mountains

Absorbs the perfume of sandal from the moist leaves and branches,

So you come to resemble whomever you follow.*

(*In this chapter, Patrul Rinpoche gives a verse summary of each point, without citing any particular source. These verses are to help the reader or listener to remember them. Direct oral transmission has always had an important place in Buddhism, and Tibetans regularly commit whole volumes of the scriptures to memory. This training enables them to remember oral teachings in detail. The systematic structure of this text, for instance, is in part to enable practitioners to have the instructions constantly available in their minds.)

As times have degenerated, nowadays it is difficult to find a teacher who has everyone of the qualities described in the precious tantras. However, it is indispensable that the teacher we follow should possess at least the following qualities.

He should be pure, never having contravened any of the commitments or prohibitions related to the three types of vow – the external vows of the Pratimoksa, the inner vows of the Bodhisattva and the secret vows of the Secret Mantrayana, He should be learned, and not lacking in knowledge of the tantras, sutras and sastras. Towards the vast multitude of beings, his heart should be so suffused with compassion that he loves each one like his only child. He should be well versed in ritual practices – outwardly, of the Tripitaka and, inwardly, of the four sections of tantras. By putting into practice the meaning of the teachings, he should have actualized in himself all the extraordinary achievements of riddance and realization. He should be generous, his language should be pleasant, he should teach each individual according to that person’s needs and he should act in conformity with what he teaches; these four ways of attracting beings enable him to gather fortunate disciples around him.

All the qualities complete according to purest Dharma

Are hard to find in these decadent times.

But trust the teacher who, based on pure observance of the three vows,

Is steeped in learning and great compassion,

Skilled in the rites of the infinite pitakas and tantras,

And rich in the fruit, the immaculate wisdom that comes through riddance and realization.

Drawn by the brilliant flower of his four attractive qualities

Fortunate disciples will gather like bees to follow him.

More particularly, for teachings on the profound essence of the Mantra Vajrayana pith-instructions the kind of master upon whom one should rely is as follows. As set out in the precious tantras, he should have been brought to maturity by a stream of ripening empowerments, flowing down to him through a continuous unbroken lineage. He should not have transgressed the samayas and vows to which he committed himself at the time of empowerment. Not having many disturbing negative emotions and thoughts, he should be calm and disciplined. He should have mastered the entire meaning of the ground, path and result tantras of the Secret Mantra Vajrayana. He should have attained all the signs of success in the approach and accomplishment phases of the practice, such as seeing visions of the yidam. Having experienced for himself the nature of reality, he himself should be liberated. The well-being of others should be his sole concern, his heart being full of compassion. He should have few preoccupations, for he has given up any clinging to the ordinary things of this life. Concentrating on future lives, his only, resolute thought is for the Dharma. Seeing samsara as suffering, he should feel great sadness, and should encourage the same feeling in others. He should be skilled at caring for his disciples and should use the appropriate method for each of them. Having fulfilled all his teacher’s commands, he should hold the blessings of the lineage.

The extraordinary teacher who gives the pith instructions

Has received empowerments, kept the samayas, and is peaceful;

Has mastered the meaning of the ground, path and result tantras;

Has all the signs of approach and accomplishment and is freed by realization;

Has limitless compassion and cares only for others;

Has few activities and thinks only, resolutely, of the Dharma;

Is weary of this world, and leads others to feel the same;

Is expert in methods and has the blessings of the lineage.

Follow such a teacher, and accomplishment comes swiftly.

On the other hand, there are certain kinds of teachers we should avoid. Their characteristics are as follows.

Teachers like a millstone made of wood. These teachers have no trace of the qualities arising from study, reflection and meditation. Thinking that as the sublime son or nephew of such and such a lama, they and their descendants must be superior to anyone else, they defend their caste like brahmins. Even if they have studied, reflected and meditated a little, they did so not with any pure intention of working for future lives but for more mundane reasons-like preventing the priestly fiefs of which they are the incumbents from falling into decay. As for training disciples, they are about as-well suited to fulfilling their proper function as a millstone made of wood.

Teachers like the frog that lived in a well. Teachers of this kind lack any special qualities that might distinguish them from ordinary people. But other people put them up on a pedestal in blind faith, without examining them at all. Puffed up with pride by the profits and honours they receive, they are themselves quite unaware of the true qualities of great teachers. They are like the frog that lived in a well.

One day an old frog that had always lived in a well was visited by another frog who lived on the shores of the great ocean.

“Where are you from?” asked the frog that lived in the well.

“I come from the great ocean,” the visitor replied.

“How big is this ocean of yours?” asked the frog from the well.

“It is enormous,” replied the other.

“About a quarter the size of my well?” he asked.

“Oh! Bigger than that!” exclaimed the frog from the ocean.

“Half the size, then?”

“No, bigger than that!”

“So-the same size as the well?”

“No, no! Much, much bigger!”

“That’s impossible!” said the frog who lived in the well. “This I have to see for myself.”

So the two frogs set off together, and the story goes that when the frog who lived in the well saw the ocean, he fainted, his head split apart, and he died.

Mad guides. These are teachers who have very little knowledge, never having made the effort to follow a learned master and train in the sutras and tantras. Their strong negative emotions together with their weak mindfulness and vigilance make them lax in their vows and samayas. Though of lower mentality than ordinary people, they ape the siddhas and behave as if their actions were higher than the sky.” Brimming over with anger and jealousy, they break the lifeline of love and compassion. Such spiritual friends are called mad guides, and lead anyone who follows them down wrong paths.

Blind guides. In particular, a teacher whose qualities are in no way superior to your own and who lacks the love and compassion of bodhicitta will never be able to open your eyes to what should and should not be done. Teachers like this are called blind guides.

Like brahmins, some defend their caste,

Or in pools of fear for their fief’s survival

Bathe themselves in bogus study and reflection;

Such guides are like a millstone made of wood.

Some, although no different from all ordinary folk,

Are unthinkingly sustained by people’s idiot faith.

Puffed up by profit, offerings and honours,

Such friends as these are like the well-bound frog.

Some have little learning and neglect their samayas and vows,

Their mentality is low, their conduct high above the earth,

They have broken the lifeline of love and compassion Mad guides like these can only spread more evil.

Especially, to follow those no better than yourself,

Who have no bodhicitta, attracted only by their fame,

Would be a huge mistake; and with such frauds as these

As your blind guides, you’ll wander deeper into darkness.

The Great Master of Oddiyana warns:

Not to examine the teacher

Is like drinking poison;

Not to examine the disciple

Is like leaping from a precipice.

You place your trust in your spiritual teacher for all your future lives. It is he who will teach you what to do and what not to do. If you encounter a false spiritual friend without examining him properly, you will be throwing away the possibility a person with faith has to accumulate merits for a whole lifetime, and the freedoms and advantages of the human existence you have now obtained will be wasted. It is like being killed by a venomous serpent coiled beneath a tree that you approached, thinking what you saw was just the tree’s cool shadow.

By not examining a teacher with great care

The faithful waste their gathered merit.

Like taking for the shadow of a tree a vicious snake,

Beguiled, they lose the freedom they at last had found.

After examining him carefully and making an unmistaken assessment, from the moment you find that a teacher has all the positive qualities mentioned you should never cease to consider him to be the Buddha in person.* This teacher in whom all the attributes are complete is the embodiment of the compassionate wisdom of all Buddhas of the ten directions, appearing in the form of an ordinary human simply to benefit beings.

(*To see one’s spiritual teacher as a Buddha one needs to feel:

1) that he is the Buddha in person both in the absolute and relative sense

2) that all his actions, be they spiritual or worldly, are those of a Buddha

3) that his kindness towards one exceeds that of the Buddhas

4) that he embodies the greatest of all refuges

5) that if, knowing this, one prays to him without relying on any other aid on the path one will develop the wisdom of realization.)

The teacher with infinite qualities complete

Is the wisdom and compassion of all Buddhas

Appearing in human form for beings’ sake.

He is the unequalled source of all accomplishments.

So that such a true teacher may skilfully guide the ordinary people needing his help, he makes his everyday conduct conform to that of ordinary people. But in reality his wisdom mind is that of a Buddha, so he is utterly different from everyone else. Each of his acts is simply the activity of a realized being attuned to the nature of those he has to benefit. He is therefore uniquely noble. Skilled in cutting through hesitation and doubt, he patiently endures all the ingratitude and discouragement of his disciples, like a mother with her only child.

Expediently, to guide us, he acts just like us all.

In truth he is completely different from us all.

His realization makes him the noblest of us all.

Skilled at cutting through our doubts, he bears with patience

All our discouragement and lack of gratitude.

A teacher with all these qualities is like a great ship in which to cross the vast ocean of samsara. Like a navigator, he unfailingly charts out for us the route to liberation and omniscience. Like a downpour of nectar, he extinguishes the blaze of negative actions and emotions. Like the sun and moon, he radiates the light of Dharma and dispels the thick darkness of ignorance. Like the earth, he patiently bears all ingratitude and discouragement, and his view and action are vast in their capacity. Like the wish-granting tree, he is the source of all help in this life and all happiness in the next. Like the perfect vase, he is a treasury of all the inconceivable variety of vehicles and doctrines that one could ever need. Like the wish-granting gem, he unfolds the infinite aspects of the four activities according to the needs of beings. Like a mother or father, he loves each one of all the innumerable living creatures equally, without any attachment to those close to him or hatred for others. Like a great river, his compassion is so vast that it includes all beings as infinite as space, and so swift that it can help all who are suffering and lack a protector. Like the king of mountains, his joy at others’ happiness is so steadfast that it cannot be shifted by jealousy, or shaken by the winds of belief in the reality of appearances. Like rain falling from a cloud,* his impartiality is never disturbed by attachment or aversion.

(*Rain falls from a cloud upon whatever lies beneath it, without distinction.)

He is the great ship carrying us beyond the seas of samsaric existence.

The true navigator, unerringly charting the sublime path,

The rain of nectar quenching the inferno of emotions and actions,

The sun and moon dispelling the darkness of ignorance.

He is the earth, immensely patient,

The wish-granting tree, source of help and happiness,

The perfect vase containing the treasure of the Dharma.

He provides all things, more than a wish-granting gem.

He is a father and mother, loving all equally.

His compassion is as vast and swift as a great river.

His joy is unchanging like the king of mountains.

His impartiality cannot be disturbed, like rain from a cloud.

Such a teacher is equal to all the Buddhas in his compassion and his blessings. Those who make a positive connection with him will attain Buddhahood in a single lifetime. Even those who make a negative connection with him will eventually be led out of samsara.

Such a teacher is equal to all the Buddhas.

If even those who harm him are set on the path to happiness,

On those who entrust themselves to him with sincere faith

Will be showered the bounty of the higher realms and liberation.

II. FOLLOWING THE TEACHER

Noble one, you should think of yourself as someone who is sick …

So begins the series of similes in the Sutra Arranged like a Tree. Sick people put themselves in the care of a skilful doctor. Travellers on dangerous paths entrust themselves to a courageous escort. Faced with dangers from enemies, robbers, wild beasts and the like, people look to a companion for protection. Merchants heading for lands across the ocean entrust themselves to a captain. Wayfarers taking the ferry to cross a river entrust themselves to the boatman. In the same way, to be protected from death, rebirth and negative emotions, we must follow a teacher, a spiritual friend.

As the sick man relies on his doctor,

The traveller on his escort,

The frightened man on his companion,

Merchants on their captain,

And passengers on their ferryman If birth, death and negative emotions are the enemies you fear,

Entrust yourself to a teacher.

A courageous disciple, armoured with the determination never to displease his teacher even at the cost of his life, so stable-minded that he is never shaken by immediate circumstances, who serves his teacher without caring about his own health or survival and obeys his every command without sparing himself at all-such a person will be liberated simply through his devotion to the teacher.

Those who, well armoured and steady of reason,

Serve a teacher regardless of health or of life,

Following his instructions without sparing themselves,

Will be freed by the strength of devotion alone.

To follow the teacher, you should have so much confidence in him that you perceive him as a real Buddha. You should have such discrimination and knowledge of the teachings that you can recognize the wisdom underlying his skilful actions and grasp whatever he teaches you. You should feel immense loving compassion for all those who are suffering with no one to protect them. You should respect the vows and samayas that your teacher has told you to keep, and should be peaceful and controlled in all your deeds, words and thoughts. Your outlook should be so broad that you can accept whatever your teacher and spiritual companions may do. You should be so generous that you can give the teacher whatever you possess. Your perception of everything should be pure, not always critical and tainted. You should restrain yourself from doing anything harmful or negative, for fear of displeasing him.

Have great faith, discrimination, knowledge and compassion.

Respect the vows and samayas. Control body, speech and mind.

Be broad-minded and generous.

Have pure vision and a sense of self-restraint.

The Sutra Arranged like a Tree and other texts also tell us that when following a teacher we should be like the perfect horse,* always acting according to the teacher’s wishes in every situation, skilfully avoiding anything that would displease him, and never getting angry or resentful even when he reprimands us severely. Like a boat, we should never tire of going back and forth to take messages or do other services for him. Like a bridge, there should be nothing that we cannot bear, however pleasant or unpleasant the tasks he asks us to do. Like a smith’s anvil, we should endure heat, cold and all other difficulties. Like a servant we should obey his every command. Like a sweeper,** we should never be proud but take the lowest position. Like a bull with broken horns, we should abandon arrogance and respect everyone.

(*The perfect horse is one of the possessions of the universal monarch. It knows his wishes before he expresses them. Here the ideal disciple is aware of the intentions of his teacher and in consequence acts appropriately.)

(**In the Indian caste system the sweeper had a very low status, and was expected to behave deferentially to all.)

Be skilled in never displeasing the teacher,

And never resent his rebukes, like the perfect horse.

Never be tired of coming and going, like a boat.

Bear whatever comes, good or bad, like a bridge.

Endure heat, cold and whatever else, like an anvil.

Obey his every order, like a servant.

Cast off all pride, like a sweeper,

And be free of arrogance, like a bull with broken horns.

This, the pitakas say, is how to follow the teacher.

There are three ways to please the teacher and serve him. The best way is known as the offering of practice, and consists of putting whatever he teaches into practice with determination, disregarding all hardship. The middling way is known as service with body and speech, and involves serving him and doing whatever he needs you to do whether physically, verbally or mentally. The lowest way is by material offerings, which means to please your teacher by giving him material goods, food, money and so forth.

To offer what wealth you may have to the Fourth Jewel,*

To honour and serve him with body and speech,

Not one of these actions will ever be wasted.

But out of the three ways to please him, practice is best.

There are three ways to please the teacher and serve him. The best way is known as the offering of practice, and consists of putting whatever he teaches into practice with determination, disregarding all hardship. The middling way is known as service with body and speech, and involves serving him and doing whatever he needs you to do whether physically, verbally or mentally. The lowest way is by material offerings, which means to please your teacher by giving him material goods, food, money and so forth.

(*The teacher, as the embodiment of the Three Jewels, is considered to be the Fourth Jewel.)

However incomprehensibly the teacher may behave, always maintain pure perception, and recognize his way of doing things as his skilful methods.

The great pandita Naropa had already become highly learned and accomplished. But his yidam told him that his teacher from previous lives was the great Tilopa, and that to find him he should travel to eastern India. Naropa set off immediately, but upon arriving in the east he had no idea where to find Tilopa. He asked the local people but they knew nothing.

“Is there nobody in these parts named Tilopa?” he insisted.

“There is someone called Tilopa the Outcaste, or Tilopa the Beggar.”

Naropa thought, “The actions of siddhas are incomprehensible. That might be him.” He asked where Tilopa the Beggar lived.

“By that ruined wall over there, where the smoke is coming from,” they

replied.

When he got to the place that had been pointed out, he found Tilopa seated in front of a wooden tub of fish, of which some were still alive and some dead. Tilopa took a fish, grilled it over the fire and put it in his mouth, snapping his fingers. Naropa prostrated himself before him and asked Tilopa to accept him as a disciple.

“What are you talking about?” Tilopa said. “I’m just a beggar!” But Naropa insisted, so Tilopa accepted him.

Now, Tilopa was not killing those fish just because he was hungry and could find nothing else to eat. Fish are completely ignorant of what to do and what not to do, creatures with many negative actions, and Tilopa had the power to free them. By eating their flesh he was making a link with their consciousness, which he could then transfer to a pure Buddhafield.* Similarly, Saraha lived as an arrowsmith, Savaripa as a hunter, and most of the other mighty siddhas of India, too, adopted very lowly lifestyles, often those of outcastes. It is therefore important not to take any of your teacher’s actions in the wrong way; train yourself to have only pure perception.

(*The snapping of the fingers is part of a practice for transferring the consciousness of another being to a pure realm. The practice of transference (phowa).)

The monk Sunaksatra was the Buddha’s half-brother. He served him for twenty-four years, and knew by heart all the twelve categories of teachings in the pitakas.* But he saw everything the Buddha did as deceitful, and eventually came to the erroneous conclusion that, apart from an aura six feet wide, there was no difference between the Buddha and himself.

(*Pitakas: the three sections of the Buddha’s teachings.)

Apart from that light around your body six feet wide,

Never have I seen, in twenty-four years as your servant,

Even a sesame seed’s worth of special qualities in you.

As for the Dharma, I know as much as you-and will no longer be your servant!

So saying, he left. Thereafter, Ananda became the Buddha’s personal attendant. He asked the Buddha where Sunaksatra would be reborn.

“In one week’s time,” the Buddha replied, “Sunaksatra’s life will come to an end and he will be reborn as a preta in a flower garden.”

Ananda went to see Sunaksatra and told him what the Buddha had said. Sunaksatra thought to himself, “Sometimes, those lies of his come true, so for seven days I had better be very careful. At the end of the week, I’ll make him eat his words.” He spent the week fasting. On the evening of the seventh day, his throat felt very dry, so he drank some water. But he could not digest the water properly, and died. He was reborn in a flower-garden as a preta with all nine marks of ugliness.

Whenever you see faults in anything your sublime teacher does, you should feel deeply embarrassed and ashamed of yourself. Reflecting that it is your own mental vision that is impure, and that all his actions are utterly flawless and unerring, strengthen your pure perception of him and increase your faith.

Without having mastered your own perceptions,

To look for mistakes in others is an immeasurable error.

Although he knew the twelve kinds of teachings by heart,

The monk Sunaksatra, consumed by the power of evil,

Saw the Buddha’s actions as deceitful.

Think about this carefully and correct yourself.

When the teacher seems to be furious with you, do not get angry. Instead, remind yourself that he must have glimpsed some fault in you and seen that this is the moment to correct it with such an outburst. When his anger has abated, go to him, confess your faults and vow not to repeat them.

If your teacher appears angry, conclude that he has seen

A fault in you, ripe for correction with his rebukes.

Confess and vow never to repeat it.

Thus, the wise will not fall under the power of Mara.

In the presence of your teacher, stand up at once whenever he does, instead of just remaining seated. When he sits down, enquire after his well-being. When you think there might be something he needs, at the right moment bring him whatever would please him.

When walking with him as his attendant, avoid walking in front of him as that would mean turning your back on him. Do not walk behind him, however, because you would be treading on his footprints.* Nor should you walk to his right, since that would be assuming the place of honour Instead, keep respectfully to his left and slightly behind. Should the road be hazardous, it would not then be wrong to ask his permission to go ahead.

(*As the spiritual teacher is Buddha, the place where his foot has trodden is blessed.)

As for the teacher’s seat and his conveyance, never tread on his cushion and do not mount upon or ride his horse. Do not open doors violently or slam them shut; handle them gently. Abstain from all expressions of vanity or discontent in his presence. Also avoid lying, unconsidered or insincere words, laughing and joking, playing the fool, and unnecessary or irrelevant chat. Learn to behave in a controlled manner, treating him with respect and awe, and never drifting into casualness.

Do not remain seated when the teacher stands up;

When he sits, solicitously bring him all he needs.

Walk with him neither in front, behind nor on the right.

To disrespect his mount or seat will spoil your merit.

Do not slam doors; do not posture vainly or scowl;

Avoid lies, laughter, ill-considered and irrelevant talk.

Serve him with composure of body, speech, and mind.

Should there be people who criticize or hate your teacher, do not treat them as your friends. If you are capable of changing the attitude of anyone who has no faith in him or who disparages him, then you should do so. But if that is impossible, avoid being too open or having familiar conversations with such people.

Do not treat as friends those who criticize

Or hate your teacher. Change their mind if you can.

If you speak freely with them, the powerful influence

Of their wrong action will harm your own samaya.

However much time you have to spend with your teacher’s entourage or with your vajra brothers and sisters, never feel weary or irritated with them; be easy to be with, like a comfortable belt. Swallow your self importance and join in with whatever there is to be done, mixing easily like salt in food. When people speak harshly to you or pick quarrels, or when the responsibilities you have to assume are too great, be ready to bear anything, like a pillar.

Like a belt, be a comfortable companion;

Like salt, be easily mixed in;

Like a pillar, untiringly bear any load;

Serve thus your vajra brothers and your teacher’s attendants.

III. EMULATING THE TEACHER’S REALIZATION* AND ACTIONS

(*To learn the thoughts and actions of the teacher means to acquire all the qualities of his body, speech and mind. If one does not first acquire the realization of the teacher, to emulate his actions would be hypocrisy.)

When you are perfectly versed in how to follow your teacher, you should be like a swan gliding smoothly on an immaculate lake, delighting in its waters without making them muddy; or like a bee in a flower garden, taking nectar from the flowers and leaving without spoiling their colour or fragrance. Doing whatever he says without ever feeling bored or tired, be receptive to your teacher and through your faith and steadfastness make sure that you absorb all his qualities of knowledge, reflection and meditation, like the contents of one perfect vessel being poured into another.

Like a swan swimming on a perfect lake,

Or a bee tasting the nectar of flowers,

Without ever complaining, but always receptive to him,

Always wait upon your teacher with exemplary conduct.

Through such devotion you will experience all his qualities.

Whenever your sublime teacher accumulates great waves of merit and wisdom through his Bodhisattva activities, your own participation with the least material offering or effort of body or speech, or even just your offering of joy at the slightest thing he does, will bring you as much merit as springs from his own unsurpassable intention.

Once there were two men travelling to central Tibet. The only food that one of them had was a handful of brown tsampa made from beans. He gave it to his companion, mixing it with the other’s copious supply of white barley tsampa. Several days later, the better-off traveller said to his fellow-voyager, “Your tsampa is probably finished by now.”

“Let’s have a look,” the other said. So they did, and there was still some bean-tsampa left. Although they checked many times, the bean-tsampa was never finished, so that in the end they had to share all the tsampa equally.

Likewise, simply by offering a small material contribution to someone else’s positive action, or by participating physically or verbally, you can attain as much merit as they do. Specifically, to serve the teacher’s daily needs, to carry messages for him or even just to sweep his room are an infallible way to accumulate merit, so try to do such things as much as you can.

All action consistent with the aims of a holy teacher

Truly engaged in the activity of bodhicitta

And accumulating merit and wisdom, all efforts

To serve him, carry his messages or even sweep his floor,

Will be fruitful – this is the best path of accumulating.

Of all the paramount sources of refuge or opportunities for accumulating merit there is none greater than the teacher. Especially while he is giving an empowerment or teaching, the compassion and blessings of all the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas of the ten directions pour into his sacred person and he becomes indivisibly one with all the Buddhas. At such a time, therefore, offering him even a mouthful of food is more powerful than hundreds or thousands of offerings at other times.

In the deity practices of the generation phase, there are many different forms of particular deities on which to meditate, but the nature of all of them is nothing other than your own root teacher. If you know that, the blessings will come swiftly. All the ways in which wisdom develops in the perfection phase depend only on the power of your devotion to your teacher and of his blessings, and consist of giving birth to the wisdom of the teacher’s realization within yourself. The essence of what has to be realized at all stages of practice, including those of the generation and perfection phases, is therefore embodied in the teacher himself. That is why all sutras and tantras describe him as being the Buddha in person.

Why is he the refuge and the field of merit?

Because the outer and inner yogas of accomplishing the teacher

Contain the essence of what is to be realized through the generation and perfection phases. That is why all siitras and tantras say he is the Buddha himself.

Although the wisdom mind of a sublime teacher is inseparable from that of all the Buddhas, in order to guide us, his disciples, impure as we are, he has appeared in ordinary human form. So, while we have him here in person, we must try our best to do whatever he says and to unite our minds with his through the three kinds of service.

There are people who, instead of serving, respecting and obeying their teacher while he was still alive, profess now that he has passed away to be meditating on a picture someone has made of him. There are others who claim to be absorbed in the contemplation of the natural state and look for all kinds of profundities elsewhere, instead of praying with devotion that they may receive in themselves the qualities of freedom and realization of the teacher’s wisdom mind. This is known as “practising at odds with the practice.”

Meeting and being guided by our teacher in the intermediate state can only take place because of a connection already created by our own limitless devotion and the power of the teacher’s compassion and prayers. It is not that the teacher comes physically. So, if you lack devotion, however perfect the teacher may be, he will not be there to guide you in the intermediate state.

Most fools take his portrait and meditate on that

But do not honour him while he is present in person.

They claim to meditate on the natural state, but do not know the teacher’s mind.

What an affliction to practise at odds with the practice!

With no devotion, to meet the teacher in the intermediate state would be miraculous!

In the first place, you should take care to check the teacher. This means that before becoming committed to him through empowerments and teachings, you should examine him with care. Should you find that he has all the characteristics of a teacher, then follow him. If some of them are lacking, do not follow him. But, from the moment you start to follow him, learn to have faith in him and see him with pure perception, thinking only of his virtues and seeing whatever he does as positive. Looking for flaws in him will only bring you inconceivable ills.

To examine the teacher in a general sense means to check whether or not he has all the qualities described in the sutras and tantras. In particular, what is absolutely necessary is that he should have bodhicitta, the mind of enlightenment. So examining a teacher could be condensed into just one question: does he or does he not have bodhicitta? If he does, he will do whatever is best for his disciples in this life and in lives to come, and their following him cannot be anything but beneficial. The Dharma taught by such a teacher is connected with the Great Vehicle, and can only lead along the authentic path. On the other hand, a teacher who lacks bodhicitta still has selfish desires, and so cannot properly transform the attitudes of his disciples. The Dharma he teaches, however profound and marvellous it may seem, will end up being useful only for the ordinary concerns of this life. This one question therefore epitomizes all the other points to be checked in a teacher. If a teacher’s heart is filled with bodhicitta, follow him, however he might appear externally. If he lacks bodhicitta, do not follow him, however excellent his disillusionment with the world, his determination to be free, his assiduous practice and his conduct may at first appear.

For ordinary people like us, however, no amount of careful examination can reveal to us the extraordinary qualities of those sublime beings who hide their true nature. Meanwhile, charlatans pretending to be saints abound, skilled in the art of deception. The greatest of all teachers is the one with whom we are linked from former lives. With him, examination is superfluous. Simply to meet him, simply to hear his voice – or even just his name – can transform everything in an instant and stir such faith that every hair on our bodies stands on end.

Rongton Lhaga told Jetsun Milarepa, “The lama of your past lives is that best of all beings, the king of translators known as Marpa. He lives in a hermitage in Trowolung in the South. Go and see him!”

Hearing the name of Marpa alone was enough to arouse in Milarepa an extraordinary faith from the very depth of his being. He thought, “I must meet this lama and become his disciple, if it costs me my life.” He tells us that on the day they were to meet, Marpa had come out on the road to look out for him but was ostensibly just ploughing a field. When Mila first saw him, he did not recognize him as his teacher. Nevertheless for an instant all his restless ordinary thoughts ceased and he stood transfixed.

Generally speaking, the teacher we meet is determined by the purity or impurity of our perceptions and the power of our past actions. So, whatever sort of person he may be, never cease to consider as a real Buddha the teacher through whose kindness you received the Dharma and personal guidance. For without the right conditions created by your past actions you would never have had the good fortune of meeting an excellent teacher. Moreover, if your perceptions were impure, you could even meet the Buddha in person and still be unable to see the qualities he had. The teacher whom you have met by the power of your past actions, and whose kindness you have received, is the most important of all.

In the middle phase, actually following the teacher, obey him in all things and disregard all hardships, heat, cold, hunger, thirst and so on. Pray to him with faith and devotion. Ask his advice on whatever you may be doing. Whatever he tells you, put it into practice, relying on him totally.

The final phase, emulating the teacher’s realization and actions, consists in carefully examining the way he behaves and doing exactly as he does. As the saying goes, “Every action is an imitation; he who imitates best, acts best.” It could be said that the practice of Dharma is to imitate the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas of the past. As the disciple is learning to be like his teacher, he will need to assimilate truly the latter’s realization and way of behaving. The disciple should be like a tsa-tsa from the mould of the teacher. Just as the tsa-tsa faithfully reproduces all the patterns engraved on the mould, in the same way the disciple should make sure he or she acquires qualities identical with, or at least very close to, whatever qualities the teacher has.

Anyone who first examines his teacher skilfully, then follows him skilfully, and finally emulates his realization and actions skilfully will always be on the authentic path, come what may.

In the beginning, skilfully examine the teacher;

In the middle, skilfully follow him;

In the end, skilfully emulate his realization and action.

A disciple who does that is on the authentic path.

Once you have met a noble spiritual friend with all the requisite qualities, follow him without any concern for life or limb – just as the Bodhisattva Sadaprarudita followed Bodhisattva Dharmodgata, the great pandit Naropa followed the supreme Tilopa, and Jetsun Mila followed Marpa of Lhodrak.

Bodhisattva Sadaprarudita and Dharmodgata

First, here is the story of how Bodhisattva Sadaprarudita became the disciple of Dharmodgata.* Sadaprarudita was looking for the Prajnaparamita, the teachings on transcendent wisdom.)

(*The name Sadaprarudita means “Ever Weeping.” Dharmodgata means “Sublime Dharma.”)

One day, his quest led him to a solitary wasteland, where he heard a voice from the skies saying, “O fortunate son, go towards the east and you will hear the Prajnaparamita, Go without caring about bodily fatigue, sleep or lethargy, heat or cold, whether by day or by night. Look neither to the right nor to the left. Before long you will receive the Prajnaparamita, either contained in books or from a monk who embodies and teaches the Dharma. At that time, fortunate son, follow and stick to the one who teaches you the Prajnaparamita, consider him your teacher and venerate his Dharma. Even if you see him enjoying the five pleasures of the senses, realize that Bodhisattvas are skilled in means, and never lose your faith.”

At these words, Sadaprarudita set out towards the east. He had not gone far when he realized that he had forgotten to ask the voice how far he should go – and so he had no idea how to find his Prajnaparamita teacher. Weeping and lamenting, he vowed to ignore fatigue, hunger, thirst and sleep, day or night until he had received the teaching. He was stricken, like a mother who has lost her only child. He was obsessed with a single question: when would he hear the Prajnaparamita?

At that moment, the form of a Tathagata appeared before him and praised the quest for Dharma. “Five hundred leagues from here,” the Tathagata added, “there is a city called City of Fragrant Breezes. It is made of the seven precious substances. It is surrounded by five hundred parks and possesses all the perfect qualities. In the centre of that city, at the crossroads of four avenues, is the abode of Bodhisattva Dharmodgata. It too is made of the seven precious substances, and is one league in circumference. There, in the gardens and other places of delight, lives the Bodhisattva, the great being Dharmodgata, with his entourage. In the company of sixty-eight thousand women he enjoys the pleasures of the five senses, over which he has total mastery, blissfully doing whatever he likes. Throughout past, present and future, he teaches the Prajnaparamita to those who dwell there. Go to him, and you will be able to hear the teachings on Prajnaparamita from him!”

Sadaprarudita could now think of nothing except what he had heard. From the very spot where he was standing, he could hear the Bodhisattva Dharmodgata teaching the Prajnaparamita. He experienced numerous states of mental concentration. He perceived the different worlds in the ten directions of the universe, and saw innumerable Buddhas teaching the Prajnaparamita, They sang the praises of Dharmodgata before disappearing. Full of joy, faith and devotion for Bodhisattva Dharmodgata, Sadaprarudita wondered how he might come into his presence.

“I am poor,” thought he. “I have nothing with which to honour him, no clothes or jewels, no perfumes or garlands, nor any of the other objects with which to pay respect to a spiritual friend. So I shall sell the flesh of my own body and, with the money I receive for it, I will honour the Bodhisattva Dharmodgata. Throughout beginningless samsara, I have sold my flesh innumerable times; an infinite number of times, too, I have already been cut to pieces and destroyed in the hells where my own desires had dragged me – but it was never to receive a teaching like this or to honour such a sublime teacher!”

He went to the middle of the market place and started calling out, “Who wants a man? Who wants to buy a man?”

But evil spirits, jealous that Sadaprarudita was undergoing such trials for the sake of the Dharma, made everyone deaf to his words. Sadaprarudita, finding no one to buy him, went to a corner and sat there weeping, tears pouring from his eyes.

Indra, king of the gods, then decided to test his determination. Taking the form of a young brahmin, he appeared before Sadaprarudita and said, “I do not need a whole man. I need only some human flesh, some human fat and some human bone marrow to make an offering. If you can sell me that, I’ll pay you for it.”

Overjoyed, Sadaprarudita took up a sharp knife and cut into his right arm till the blood spurted out. He then cut off all the flesh from his right thigh, and, as he was preparing to smash the bones against a wall, the daughter of a rich merchant saw him from the top story of her house and rushed down to him.

“Noble one, why are you inflicting such pain upon yourself?” she asked.

He explained that he wished to sell his flesh so that he might make an offering to the Bodhisattva Dharmodgata.

When the young girl asked him what benefit he would obtain from such homage, Sadaprarudita replied, “He will teach me the skilful methods of the Bodhisattvas and the Prajnaparamita. If I then train myself in those, I shall attain omniscience, possess the many qualities of a Buddha and be able to share the precious Dharma with all beings.”

“It is surely true,” said the girl, “that each of those qualities deserves an offering of as many bodies as there are grains of sand in the Ganges. But please do not hurt yourself so! I shall give you whatever you need to honour the Bodhisattva Dharmodgata and come with you myself to see him. In so doing, I will create the root of merit which will enable me to attain the same qualities, too.”

When she finished speaking, Indra reassumed his own form and said to Sadaprarudita, “I am Indra, King of the Gods. I came to test your determination. I shall give you whatever you want; you have only to ask.”

“Bestow upon me the unsurpassable qualities of the Buddhas!” Sadaprarudita replied.

“That I cannot grant you,” said Indra. “Such things do not fall within my domain.”

“In that case, there is no need for you to trouble yourself about making my body whole again,” said Sadaprarudita. “I shall invoke the blessings of the truth. By the blessings of the Buddhas’ prediction that I will never return into samsara, by the truth of my supreme and unshakeable determination, and by the truth of my words, may my body resume its former state!”

At these words, his body became exactly as it had been before. And Indra disappeared.

Sadaprarudita went with the merchant’s daughter to her parents’ house and there told them his tale. They provided him with the numerous materials he would need for his offering. Then he, together with the merchant’s daughter and her parents, accompanied by five hundred female attendants and their whole retinue, set out in carriages towards the east, and arrived in the City of Fragrant Breezes. There he saw the Bodhisattva Dharmodgata preaching the Dharma to thousands of people. The sight filled him with the bliss that a monk experiences when immersed in meditative absorption. The entire party stepped down from their carriages and went to meet Dharmodgata.

Now Dharmodgata, at that time, had built a temple to the Prajnaparamita. It was made of the seven precious substances, and was decorated with red sandalwood and covered with a filigree of pearls. In each of the four directions had been placed wish-granting gems as lamps and silver censers from which wafted fragrant offerings of black aloe-wood incense. At the centre of the temple were four jewelled coffers containing the volumes of the Prajnaparamita, made of gold and written in ink of lapis lazuli.

Seeing both gods and men making offerings, Sadaprarudita made enquiries and then, accompanied by the daughter, the merchant and the five hundred attendants, made excellent offerings too.

They then approached Dharmodgata, who was giving teaching to his disciples, and honoured him with all their offerings. The merchant’s daughter and her maidens took the vows of sublime bodhicitta. Sadaprarudita asked him where the Buddhas he had seen before had come from and where they had gone. Dharmodgata answered with the chapter explaining that Buddhas neither come nor go.* He then left his seat and went to his own quarters, where he remained in the same continuous state of concentration for seven years.

(*This means that Buddhas are not bound by concepts of place.)

Throughout this whole period, Sadaprarudita, the merchant’s daughter and the five hundred servants renounced both sitting and lying down, staying permanently on their feet. As they stood still or walked around, their minds dwelt only on the moment when Dharmodgata would arise from his concentration and teach the Dharma once more.

When those seven years were nearly at an end, Sadaprarudita heard the gods announcing that in seven days’ time Bodhisattva Dharmodgata would arise from his state of concentration and start teaching again. With the five hundred serving maidens he swept, for one league in every direction, the area where Dharmodgata was going to teach. When he started to sprinkle water on the ground to settle the dust, Mara made all the water disappear. So Sadaprarudita cut open his veins and sprinkled his own blood on the ground, and the merchant’s daughter and her five hundred attendants did the same. Indra, King of the gods, transformed their blood into the red sandalwood of the celestial realms.

At last, Bodhisattva Dharmodgata arrived and sat upon the lion-throne that Sadaprarudita and the others had so perfectly set up. He expounded the Prajnaparamita. Sadaprarudita experienced six million different states of concentration and had the vision of an infinite number of Buddhas – a vision which never again left him, even in his dreams. It is said that he now dwells in the presence of the perfect Buddha called He who Proclaims the Dharma with Inexhaustible Melodious Voice.

Tilopa and Naropa

While following Tilopa, the great pandita Naropa also underwent immeasurable difficulties. As we saw earlier, Naropa met Tilopa, who was living like a beggar, and asked him to accept him as his disciple. Tilopa granted this request and took him along wherever he went, but never taught him any Dharma.

One day, Tilopa took Naropa to the top of a nine-storey tower and asked: “Is there anyone who can leap from the top of this building to obey his Master?”

Naropa thought to himself, “There is nobody else here, so he must mean me.” He jumped from the top of the building and his body crashed to the ground, causing him tremendous pain and suffering.

Tilopa came down to him and asked, “Are you in pain?”

“It’s not just the pain,” groaned Naropa. “I am not much more than a corpse …” But Tilopa blessed him, and his body was completely healed. Tilopa led Naropa off again on their journey.

“Naropa, make a fire!” Tilopa ordered him one day.

When the fire was blazing, Tilopa prepared many long splinters of bamboo, oiling them and putting them in the fire to harden.

“If you’re going to obey your teacher’s orders, you’ll also have to undergo trials like this,” he said, and pushed the splinters under the nails of his disciple’s fingers and toes.

Naropa’s joints all became completely rigid and he experienced unbearable pain and suffering. The Guru then left him. When he returned several days later, he pulled out the splinters and huge quantities of blood and pus streamed from Naropa’s wounds. Once again Tilopa blessed him and set off with him again.

“Naropa,” he said another day, “I’m hungry. Go and beg some food for me!”

Naropa went to a spot where a large crowd of farm labourers were busy eating, and from them he begged a skull-cup* full of soup which he took back to his teacher. Tilopa ate it with enormous relish and seemed to be delighted.

(*A skull cup. The top of a skull is used by some yogis as a bowl. It symbolizes egolessness.)

Naropa thought, “In all the long time I have served him, I have never seen my teacher so happy. Perhaps if I ask again I can get some more.”

He set off to beg again, skull-cup in hand. By this time the workers had gone back to their fields, leaving their left-over soup where it had been before.

“The only thing to do is to steal it,” Naropa thought to himself, and he took the soup and ran off with it.

But the labourers saw him. They caught him and beat him up, leaving him for dead. He was in such pain that he could not get up for several days. Again his teacher arrived, blessed him and took to the road with him as before.

“Naropa,” he said another day, “I need a lot of money.”? Go and steal me some.”

So Naropa went off to steal money from a rich man, but was caught in the act. He was seized, beaten, and again left for dead. Several days passed before Tilopa arrived and asked him, “Are you in pain?” Receiving the same answer as before, he blessed Naropa, and off they went again.

Naropa underwent twelve major and twelve minor hardships like these-twenty-four hardships that he had to undergo in one lifetime.

Finally, they were at an end.

One day, Tilopa said, “Naropa, go and fetch some water. I’ll stay here and make the fire.”

When Naropa came back carrying the water, Tilopa jumped up from the fire he had been making and grabbed Naropa’s head with his left hand.

“Show me your forehead,” he ordered.

With his right hand he took off his sandal and hit his disciple on the forehead with it. Naropa lost consciousness. When he came to, all the qualities of his teacher’s wisdom mind had arisen within him. Teacher and disciple had become one in realization.

As the twenty-four trials undergone by the great pandita Naropa were, in fact, his teacher’s instructions, they became the skillful means by which his obscurations were eliminated. They appear to be just pointless hardships that nobody would think of as Dharma. Indeed, the teacher had not uttered a word of teaching and the disciple had not done a moment of

practice, not even a single prostration. However, once Naropa had met an accomplished siddha, he had obeyed his every command regardless of all difficulties, and in so doing achieved the purification of his obscurations so that realization awakened in him.

There is no greater Dharma practice than obeying one’s teacher. The benefits are immense, as we can see here. On the other hand, to disobey him, even a little, is an extremely grave fault.

Once Tilopa forbade Naropa to accept the post of pandita-gatekeeper at Vikramasila*. But when Naropa arrived in Magadha sometime later, one of the panditas who held this position had died. Since there was no one else capable of debating with the tirthikas, they all begged Naropa to take the post of protector of the northern gate, and pressed him insistently until he accepted. However, when a tirthika presented himself for debate, Naropa argued with him for days on end without being able to defeat him. He prayed to his teacher until finally one day Tilopa appeared to him, looking at him with a piercing gaze.

(*Vikramasila – One of the three great monastic universities of Buddhist India, the others being Nalanda and Odantapuri. The post of “pandita-gatekeeper” of the “gates,” or departments, at teach cardinal point was given to the scholars most able to defend the Buddhist philosophical position against the challenges of non-Buddhist thinkers presenting themselves for debate. Intense and formalized debating between proponents of different schools of thought was characteristic of this period of high civilization in Northern India.)

“You don’t have much compassion-why didn’t you come earlier?”

Naropa complained.

“Did I not forbid you to take this post of gatekeeper?” Tilopa retorted.

“Nevertheless, while you debate, visualize me above your head and make

the threatening gesture at the tirthika!”

Naropa did as Tilopa had told him, won his debate and put an end to

all the arguments of the tirthikas.

Marpa and Milarepa

Finally, here is how Jetsun Milarepa followed Marpa of Lhodrak. In the region of Ngari Gungthang, there lived a rich man by the name of Mila Sherab Gyaltsen. This man had a son and a daughter, and it was the son, whose name was Mila Thopa-ga, “Mila Joy to Hear,” who was to become Jetsun Mila. When the two children were still small, their father died. Their uncle, whose name was Yungdrung Gyaltsen, appropriated all their wealth and possessions. The two children and their mother, left with neither food nor money, were forced to undergo many hardships. Mila learned the arts of casting spells and making hailstorms from the magicians Yungton Throgyal of Tsang and Lharje Nupchung, and brought about the death of his uncle’s son and daughter-in-law together with thirty-three other people by making the house collapse. When all the local people turned angrily against him, he caused such a hailstorm that the hail lay on the ground as deep as three courses of a clay wall*.

(*About three meters. In many parts of Tibet, the walls of houses were built of clay, which was compacted while wet between parallel wooden forms laid along the line of the wall, and allowed to dry. The forms would then be moved up to hold the next course of clay. The wooden boards used as forms were generally about a meter in width.)

Afterwards, repenting his misdeeds, he decided to practise Dharma. Taking the advice of Lama Yungton, he went to see an adept of the Great Perfection by the name of Rongton Lhaga, and asked him for instruction.

“The Dharma I teach,” the Lama replied, “is the Great Perfection. Its root is the conquest of the beginning, its summit the conquest of attainment and its fruit the conquest of yoga. If one meditates on it during the day, one can become Buddha that same day; if one meditates on it during the night, one can become Buddha that very night. Fortunate beings whose past actions have created suitable conditions do not even need to meditate; they will be liberated simply by hearing it. Since it is a Dharma for those of eminently superior faculties, I will teach it to you.”

After receiving the empowerments and instructions, Mila thought to himself, “It took me two weeks to obtain the main signs of success at casting spells. Seven days were enough for making hail. Now here is a teaching even easier than spells and hail-if you meditate by day you become a Buddha that day; if you meditate by night you become a Buddha that night-and if your past actions have created suitable conditions, you don’t even need to meditate at all! Seeing how I met this teaching, I obviously must be one of the ones with good past actions.”

So he stayed in bed without meditating, and thus the practitioner and the teaching parted company.

“It is true what you told me,” the lama said to him after a few days. “You really are a great sinner, and I have praised my teaching a little too highly. So now I will not guide you. You should go to the hermitage of Trowolung in Lhodrak, where there is a direct disciple of the Indian siddha Naropa himself. He is that most excellent of teachers, the king of translators, Marpa. He is a siddha of the New Mantra Tradition*, and is without rival throughout the three worlds. Since you and he have a link stemming from actions in former lives, go and see him!”

(*The tradition based on the teachings originally introduced into Tibet from India in the 8th century came to be known as the Ancient, or Nyingma, Tradition. The tradition based on the new wave of teachings introduced from the 11th century onwards was called the New, or Sarma, Tradition. Milarepa’s first teacher, Rongton Laga, belonged to the Nyingma, while Marpa was a translator and accomplished practitioner of the New Tradition teachings.)

The sound of Marpa the Translator’s name alone was enough to suffuse Mila’s mind with inexpressible joy. He was charged with such bliss that every pore on his body tingled, and immense devotion swept over him, filling his eyes with tears. He set off, wondering when he would meet his teacher face to face.

Now, Marpa and his wife had both had many extraordinary dreams, and Marpa knew that Jetsun Mila was on his way. He went down the valley to await his arrival, pretending to be just ploughing a field. Mila first met Marpa’s son, Tarma Dode, who was tending the cattle. Continuing a little further, he saw Marpa, who was ploughing. The moment Mila caught sight of him, he experienced tremendous, inexpressible joy and bliss; for an instant, all his ordinary thoughts stopped. Nonetheless, he did not realize that this was the lama in person, and explained to him that he had come to meet Marpa.

“I’ll introduce you to him myself,” Marpa answered him. “Plough this field for me.” Leaving him a jug of beer, he went off. Mila, draining the jug to the last drop, set to work. When he had finished, the lama’s son came to call him and they set off together.

When Mila was brought into the lama’s presence, he placed the soles of Marpa’s feet upon the crown of his head and cried out, “Oh, Master! I am a great sinner from the west! I offer you my body, speech and mind. Please feed and clothe me and teach me the Dharma. Give me the way to become Buddha in this life!”

“It’s not my fault that you reckon you’re such a bad man,” Marpa replied. “I didn’t ask you to pile up evil deeds on my account! What is all this wrong you have done?”

Mila told him the whole story in detail.

“Very well,” Marpa acquiesced, “in any case, to offer your body, speech and mind is a good thing. As to food, clothing and Dharma, however, you cannot have all three. Either I give you food and clothing and you look for Dharma elsewhere, or you get your Dharma from me and look for the rest somewhere else. Make up your mind. And if it’s the Dharma you choose, whether or not you attain Buddhahood in this lifetime will depend on your own perseverance.”

“If that is the case,” said Mila, “since I came for the Dharma, I will look for provisions and clothing elsewhere.”

He stayed a few days and went out begging through the whole of upper and lower Lhodrak, which brought him twenty-one measures of barley. He used fourteen of them to buy a four-handled copper pot. Placing six measures in a sack, he went back to offer that and the pot to Marpa.

When he set the barley down, it made the room shake. Marpa got up.

“You’re a strong little monk, aren’t you?” he said. “Are you trying to kill us all by making the house fall down with your bare hands? Get that sack of barley out of here!” He gave the sack a kick, and Mila had to take it outside. Later on he gave Marpa the empty pot.

(*Jetsun Mila wanted to offer the pot filled with barley. To offer an empty vessel is considered to be inauspicious.)

One day Marpa said to him: “The men of Yamdrok Taklung and Lingpa are attacking many of my faithful disciples who come to visit me from U and Tsang, and stealing their provisions and offerings. Bring hailstorms down on them! Since that is a kind of Dharma too, I will give you the instructions afterwards.”

Mila caused devastating hailstorms to fall on both these regions and then went to ask for the teachings.

“You think I’m going to give you the teachings I brought back from India at such great cost in exchange for three or four hailstones? If you really want the Dharma, cast a spell on the hill-folk of Lhodrak. They attack my disciples from Nyaloro and are always treating me with downright contempt. When there is a sign that your spell has worked, I shall give you Naropa’s oral instructions, which lead to Buddhahood in a single lifetime and body.”

When the signs of the success of the evil spell appeared, Mila asked for the Dharma.

“Huh! Is it perhaps to pay honour to your accumulation of evil deeds that you are claiming to want these oral instructions that I had to search for, never considering the risk to my own body and life-these instructions still warm with the breath of the dakinis? I suppose you must be joking, but I find this a bit too much. Anyone else but me would kill you! Now, bring those hill people back to life and return to the people of Yamdrok their harvest. You’ll get the teachings if you do-otherwise, don’t hang around me anymore!”

Mila, utterly shattered by these reprimands, sat and wept bitter tears. The next morning, Marpa came to see him.

“I was a bit rough with you last night,” he said. “Don’t be sad. I will give you the instructions little by little. Just be patient! Since you’re a good worker, I’d like you to build me a house to give to Tarma Dode, When you’ve finished, I’ll give you the instructions, and provide you with food and clothing as well.”

“But what will I do if I die in the meantime, without the Dharma?” Mila asked.

“I’ll take the responsibility of making sure that doesn’t happen,” Marpa said. “My teachings are not just idle boasting, and since you obviously have extraordinary perseverance, when you put my instructions into practice we will see if you can attain Buddhahood in a single lifetime.”

After further encouragement in the same vein, he had Mila build three houses one after the other: a circular one at the foot of the eastern hill, a semicircular one in the west and a triangular one in the north. But each time, as soon as the house was half finished, Marpa would berate Mila furiously, and make him demolish whatever he had built and take all the earth and stones he had used back to where he had found them.

An open sore appeared on Mila’s back, but he thought, “If I show it to the Master, he will only scold me again. I could show it to his wife but that would just be making a fuss.” So, weeping, but not showing his wounds, he implored Marpa’s wife to help him request the teachings.

She asked Marpa to teach him, and Marpa replied, “Give him a a good meal and bring him here!” He gave Mila the transmission and vows of refuge.

“All this,” he said, “is what is called the basic Dharma. If you want the extraordinary instructions of the Secret Mantrayana, the sort of thing you’ll to have to go through is this…” and he recounted a brief version of the life and trials of Naropa. “It’ll be difficult for you to do the same,” he concluded.

At these words Mila felt such intense devotion that his tears flowed freely, and with fierce determination he vowed to do whatever his teacher asked of him.

A few days later, Marpa went for a walk and took Mila with him as his attendant. He went south-east and, coming to a favourably situated piece of ground, he said, “Make me a grey, square tower here, nine storeys high. With a pinnacle on top, making ten. You won’t have to take this building down, and when you’ve finished I’ll give you the instructions. I’ll also give you provisions when you go into retreat to practise.”

Mila had already dug the foundations and started building when three of his teacher’s more advanced pupils came by. For fun, they rolled up a huge stone for him and Mila incorporated it in the foundations. When he had finished the first two storeys, Marpa came to see him and asked him where the stone in question had come from. Mila told him what had happened.

“My disciples practising the yoga of the two phases shouldn’t be your servants!” Marpa yelled. “Get that stone out of there and put it back where it came from!”

Mila demolished the whole tower, starting from the top. He pulled out the big foundation stone and took it back to where it had come from.

Then Marpa told him, “Now bring it here again and put it back in.”

So Mila hauled it back to the site and put it in just as before. He went on building until he had finished the seventh storey, by which time he had an open sore on his hip.

“Now leave off building that tower,” Marpa said, “and instead build me a temple, with a twelve-pillared hall and a raised sanctuary.”

So Mila built the temple, and by the time he had finished, a sore had broken out on his lower back.

At that time, Meton Tsonpo of Tsangrong asked Marpa for the empowerment of Samvara, and Tsurton Wange of Dol asked for the empowerment of Guhyasamaja, On both occasions, Mila, hoping that his building work had earned him the right to empowerment, took his place in the assembly, but all he received from Marpa were blows and rebukes and he was thrown out both times. His back was now one huge sore with blood and pus running from three places. Nevertheless, he continued working, carrying the baskets of earth in front of him instead.

When Ngokton Chodor of Shung came to ask for the Hevajra empowerment, Marpa’s wife gave Mila a large turquoise from her own personal inheritance. Using it as his offering for the empowerment, Mila placed himself among the row of candidates but, as before, the teacher scolded him and gave him a thrashing, and he did not receive the empowerment.

This time he felt that there was no further doubt: he would never receive any teachings. He wandered off in no particular direction. A family in Lhodrak Khok hired him to read the Transcendent Wisdom in Eight Thousand Verses. He came to the story of Sadaprarudita, and that made him think. He realized that, for the sake of the Dharma, he must accept all hardships and please his teacher by doing whatever he ordered.

So he returned, but again Marpa only welcomed him with abuse and blows. Mila was so desperate that Marpa’s wife sent him to Lama Ngokpa, who gave him some instructions. But when he meditated nothing came of it, since he had not received his teacher’s consent. Marpa ordered him to go back with Lama Ngokpa, and then to return.

One day, during a feast offering, Marpa severely reprimanded Lama Ngokpa and some other disciples and was about to start beating them.

Mila thought to himself, “With my evil karma, not only do I myself suffer because of my heavy faults and dense obscurations, but now I am also bringing difficulties on Lama Ngokpa and my Guru’s consort. Since I am just piling up more and more harmful actions without receiving any teaching, it would be best if I did away with myself.”

He prepared to commit suicide. Lama Ngokpa was trying to stop him when Marpa calmed down and summoned them both. He accepted Mila as a disciple, gave him much good advice and named him Mila Dorje Gyaltsen, “Mila Adamantine Victory Banner.” As he gave him the empowerment of Sarnvara, he made the mandala of its sixty-two deities clearly appear. Mila then received the secret name of Shepa Dorje, “Adamantine Laughter,” and Marpa conferred all the empowerments and instructions on him just like the contents of one pot being poured into another. Afterwards, Mila practised in the hardest of conditions, and attained all the common and supreme accomplishments.*

(*The trials that Milarepa had to undergo before receiving the teachings from Marpa, as well as being a purification of past karma, an accumulation of merit and a psychological preparation, also had a bearing on the future of his lineage, each detail having a symbolic significance which, by the principle of interdependence would affect Milarepa’s own future and that of his disciples.)

It was like this that all the panditas, siddhas and vidyadharas of the past, in both India and Tibet, followed a spiritual friend who was an authentic teacher, and by doing whatever he said achieved realization inseparable from the teacher’s own.

On the other hand, it is a very serious fault not to follow the teacher with a completely sincere mind, free from deceit. Never perceive any of his actions negatively. Never even tell him the smallest lie.

Once the disciple of a great siddha was teaching the Dharma to a crowd of disciples. His teacher arrived, dressed as a beggar. The disciple was too embarrassed to prostrate before him in front of the crowd, so he pretended not to have seen him. That evening, once the crowd had dispersed, he went to see his teacher and prostrated to him.

“Why didn’t you prostrate before?” his teacher asked.

“I didn’t see you,” he lied. Immediately, both his eyes fell to the ground. He begged forgiveness and told the truth, and with a blessing the master restored his sight.

There is a similar story about the Indian mahasiddha Krsnacarya, One day, he was sailing at sea in the company of numerous disciples, when the thought arose in his mind, “My teacher is a real siddha, but from a worldly point of view I am better than him, because I am richer and have more attendants.”

Straight away, his ship sank into the ocean. Floundering desperately in the water, he prayed to his teacher, who appeared in person and saved him from drowning. “

That was the reward for your great arrogance,” the teacher said. “Had I tried to gather wealth and attendants, I would have had them too. But I chose not to do that.”

Inexpressible multitudes of Buddhas have already come, but their compassion has not been enough to save us: we are still in the ocean of suffering of samsara. Inconceivable numbers of great teachers have appeared since ancient times, but we have not had the good fortune to enjoy their compassionate care, or even to meet them. These days, the teachings of the Buddha are coming to an end. The five degenerations are more and more in evidence, and although we have obtained human life, we are totally in the clutches of our negative actions, and confused about what to do and what not to do. As we wander like a blind man alone in an empty plain, our spiritual friends, the supreme teachers, think of us with their boundless compassion, and according to the needs of each of us appear in human form. Although in their realization they are Buddhas, in their actions they are attuned to how we are. With their skilful means they accept us as disciples, introduce us to the supreme authentic Dharma, open our eyes to what we should do and what we should not do, and unerringly point out the best path to liberation and omniscience. In truth, they are no different from the Buddha himself; but compared to the Buddha their kindness in caring for us is even greater. Always try, therefore, to follow your teacher in the right way, with the three kinds of faith.

I have met a sublime teacher, but let myself down by my negative behaviour.

I have found the best path, but I wander on precipitous byways.

Bless me and all those of bad character like me

That our minds may be tamed by the Dharma.

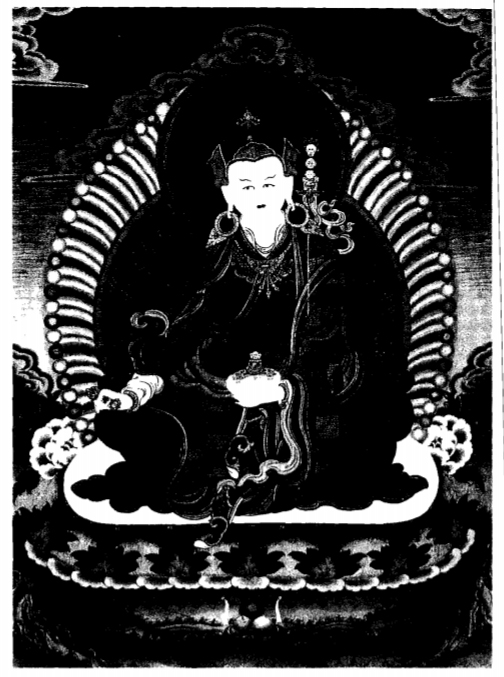

Guru Rinpoche

(Also known as Padmasambhava, the Lotus-born, he is the “Second Buddha” who established Buddhism in Tibet. He is shown here in the form known as “Prevailing Over Appearances and Existence” (Nangsi Zilnon), the name meaning that, as he understands the nature of everything that appears, he is naturally the master of all situations.)

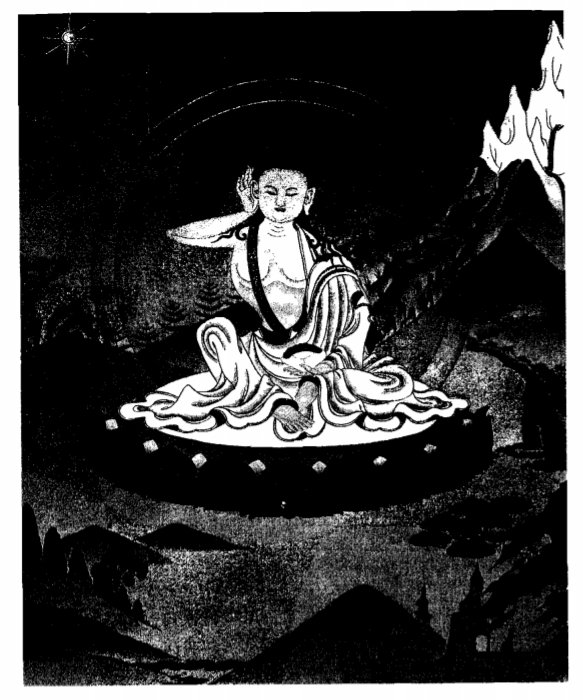

Milarepa (1040-1123)

Tibet’s most famous yogi, renowned for his ascetic lifestyle in the high mountains of Southern Tibet, his perseverance in meditation, and the spontaneous songs by which he taught hunters and villagers alike.